Unknowable Answers, Impossible Choices

As our careers get more complex, the decisions get harder and harder.

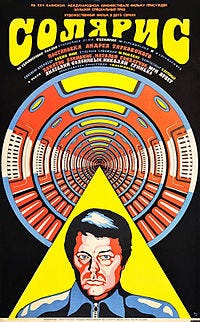

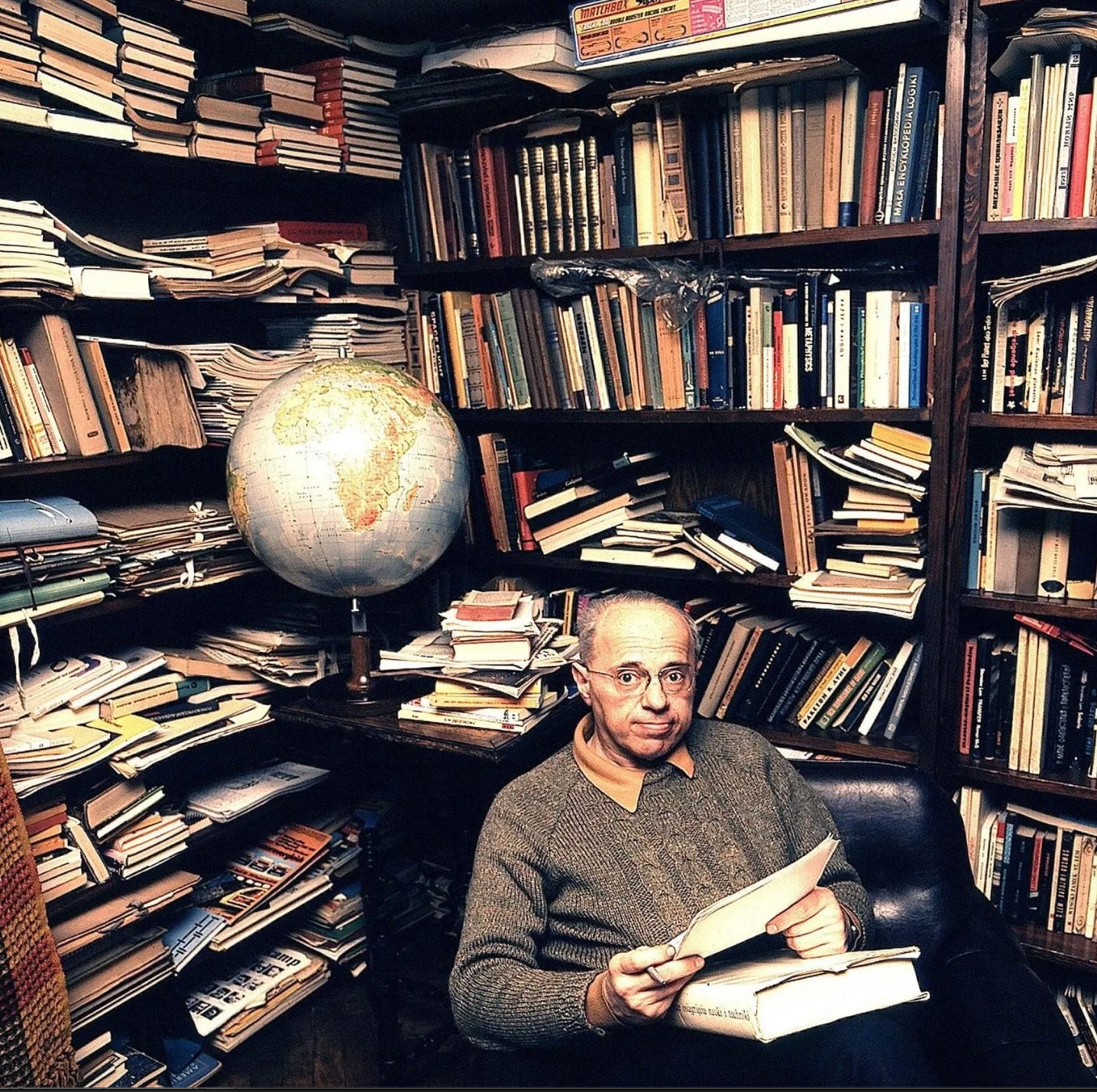

In the 1970s, Polish Science Fiction novelist Stanislaw Lem complained that the 1972 Russian movie adaptation of his 1961 novel Solaris was “weird.” It’s an odd critique considering the protagonist is, as far as we are able to determine, a sentient ocean.

The novel was adapted into feature films twice. I watched both versions recently. The mix of moralism and solipsism reminded me of topics we face frequently here on Safe @ Work. We will face them bravely here together today.

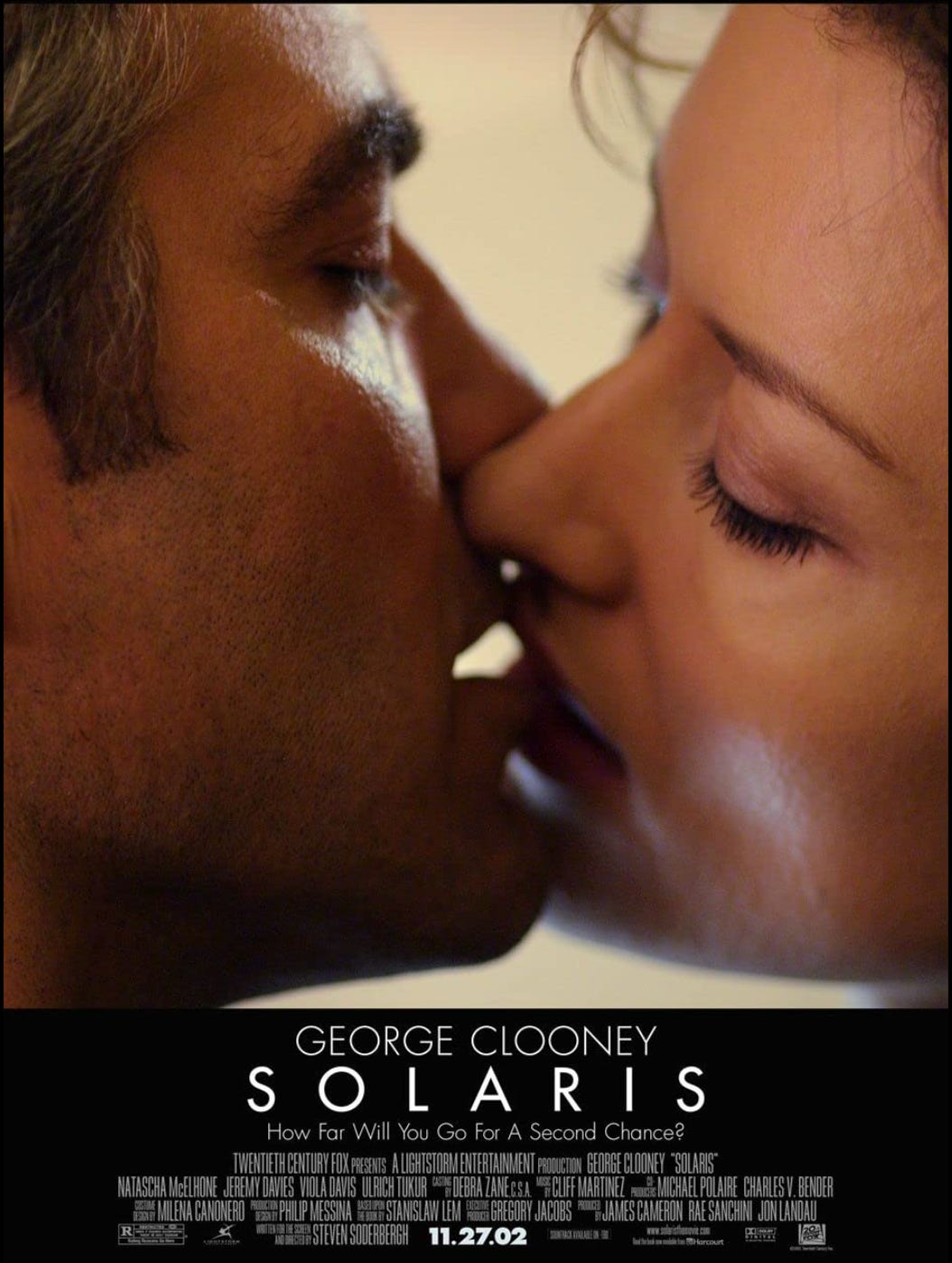

In 2002 Steven Soderbergh adapted the novel again in a big Hollywood feature film staring George Clooney. Lem was again unhappy with the result. He groused that the American Solaris was obsessed with the “erotic problems of people in outer space.” He reminded readers that “the book was entitled ‘Solaris’ and not ‘Love in Outer Space.’”

He was an extremely interesting guy (Lem, not Clooney!) He was born in 1921 in what was then Poland in a place now known as Lviv, Ukraine. Lem was of Jewish descent but a devout Atheist. He was good friends and an intellectual sparring partner of Karol Wojtyla, also known as Pope John Paul II.

The Russian Solaris, released in 1972, is 2 hours 40 minutes long (on iTunes or Amazon Freevee.) Director Andrei Tarkovsky is one of the most famous and influential in the history of cinema, known to be preoccupied with nature and memory. This film is certainly that. It is also extraordinary. On scope and scale it invites comparisons to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey which was made — amazingly — four years earlier.

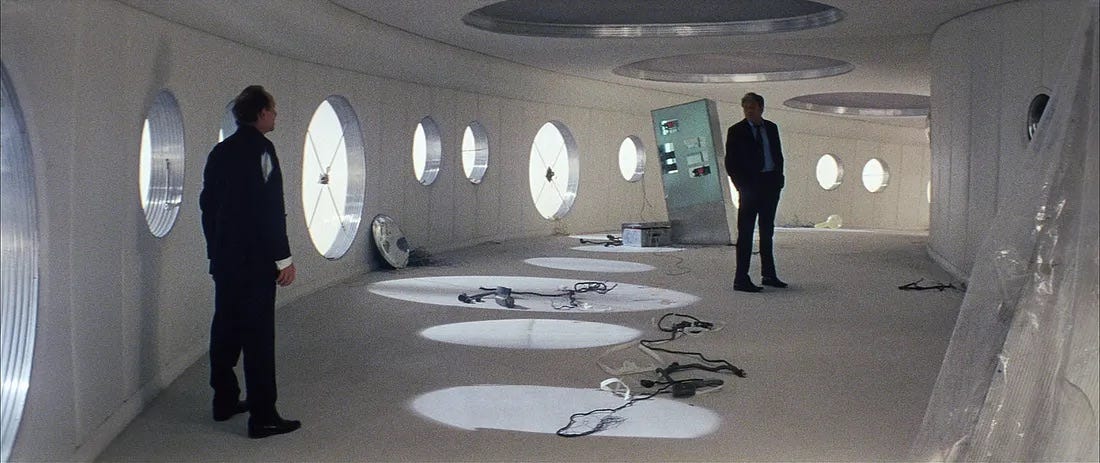

Tarkovsky’s space station is found orbiting the eponymous mysterious planet. It is not the glistening and pristine operating room of 2001’s NASA vessel. It’s also far less vertiginous, disorienting, and gimmicky. There are no talking computers. The Soviet-era interiors are brutal and beautiful, with wires sparking in disrepair. They’re unkept and littered with unexplained artifacts and broken glass because, well, reasons.

Tarkovsky felt 2001 showed too much and said too little. He wanted science fiction to have more emotional depth and less techno-utopian wizardry. Solaris achieves this masterfully. The image on the streaming services is good enough, and the experience watching it in Russian is made easy by subtitles that are, for once, large and easy-to-read.

The film is over 50 but, like me, looks and feels much younger. The sets are somehow crisp and yet worn. The plot feels very deliberately paced, mostly. The plot is mysterious, diabolical, and a little confusing. All in a good way. Some moments feel quite harrowing, and others seem a bit lost.

The style inside the space station is remarkable. The repeating rows and racks of equipment reminded me of 2001. I preferred Solaris’s grimy, smoky, vacuum-tube vibe. It’s just irresistibly realistic and appealing. I could smell the cigarette smoke and spilled vodka — my kind of place! 2001 smells like hand sanitizer, the kind of place people who want to return to office want to get away from. If I have to return to office, can I return to a 1960’s Soviet space station?

(Near the end of the movie, a very strange, very brief scene of weightlessness occurs. The effect is so glorious, effortless, and improbably romantic… it stopped my cold, dark heart for just a moment. I’m not putting a picture here because it will look terrible. You have to see it, as I did, three times.)

The ending is absolutely inexplicable. It will blow your mind. When you understand what’s happened, which you will not until you Google it, it will rip your heart out right out of your chest. Enjoy!

Moving on to the modern Solaris (on Amazon Prime Video), it’s quite a different story. Everything in this film is precise and perfect. The artistry soars, the star power is celestial, and the chemistry is delightful. It’s often described as one of Steven Soderbergh’s most underrated pictures. Does it surpasses the Russian version? No. But it’s only 99 minutes long, so as with my writing, if you hate it, at least it’s pretty short.

Thematically the picture drifts from the novel and from the Russian film. A reasonable assessment might be “love for those who are lost.” It’s a bit dark, and the tone is uneasy. It wasn’t a great pick to view alone late at night. But let’s see you try to get a couple of tweens to watch a film about “love for those who are lost” with a cast of only three actors and one sentient ocean.

Like the Russian film, it’s quite beautiful to watch. If you like beautiful brainy things, you’ll love both movies. If you want to understand the ending, watch the American movie.

But why am I writing about this? This dialogue is why, from the American film:

Chris Kelvin : What does Solaris want from us?

Gibarian : Why do you think it has to want something?

There are no answers, only choices.

What does it mean? I’ve been studying up on my Stanislaw Lem. I think Lem, an atheist, is struggling with the futility of trying to construct a moral way of life in an amoral world.

Here’s another line, this one from the Russian film:

Kris Kelvin: Shame, the feeling that will save mankind

This is a Cold War reference. I’m going to shamelessly apply it to some ethical conundrums faced by people in business situations.

You know who doesn’t have ethical crises or business coaches? Monks.

There are no moral calamities in a monastery. There are no moral compromises when all of the choices about what to do are made in advance.

The most difficult decisions in our careers occur when we’re called on to make moral compromises.

Increasingly successful people — that’s you — are required to have increasingly flexible systems for processing rectitude and virtue.

How can we reconcile our ideas about what’s right in the world with what’s best for ourselves and our families?

Tough Choices

What do I mean by choosing between what we know is right and what we know is best? Let me give you some examples.

Marlene resigned from her job. Happily she quickly found a new position. She quit because her manager was awful and the environment was toxic. The micromanagement and microaggressions required her to make compromises she just couldn’t take any more.

HR has scheduled an exit interview. Marlene has got loads of advice that says she should not tell the truth during her exit interview. Why? Because no benefit to Marlene. She may want to come back to this company some day. She doesn’t want to burn any bridges.

But now Marlene has a new problem. She is thinking about the people she’s leaving behind at this company. She is thinking about the “campsite rule.1” She wants to leave the place better than she found it. She thinks if she can sound some kind of alarm, maybe she can minimize future harm to other campers.

There are no good answers here, only choices. I told Marlene maybe she could have a private conversation with somebody in HR or a skip-level boss. There’s no guarantee to Marlene that she’ll come away from that squeaky clean.

If the manager’s behavior is abusive, ethically it’s 100% clear she should make a report to avoid future harm to others. Otherwise, if she chooses to smile through the exit interview, I support any choice Marlene makes. It’s no monastery.

Here’s another situation. Jeremy has a deadbeat client. They signed him up for six months of work. After a couple of months, they decided they didn’t like what they were seeing. So they cut him loose.

They also decided they didn’t want to pay him what they owe him. Of course that is unethical, inappropriate, unwise, and probably illegal. Still, clients who should know better do it all the time.

Depending on Jeremy’s contract, his lawyer, his patience, and emotional fortitude, maybe Jeremy will collect eventually. Maybe, maybe not.

Don’t try me. I’m not a free sample.

Deadbeats

Jeremy is pissed, and he’s daydreaming about putting it out on social media that this client is a deadbeat. In a more realistic but less satisfying scenario, he could discreetly let a few people know that these are not good businesspeople. Or he could post a review letting folks know about his experience working with them.

He’s read people saying that say you shouldn’t publicly shame a client. But why exactly do people say that? Aren’t we supposed to be looking out for each other? If he took the client’s money and didn’t deliver the work, wouldn’t the client leave a bad review on Fiverr or Upwork for Jeremy if the client wasn’t happy with him?

That is true and it really isn’t fair. For a freelancer, publicly shaming a client is bad business. That’s because clients search the internet to check their vendors’ references. Future clients will see this behavior and perceive it as unprofessional. And they’ll be right. That’s why most people choose to walk away from a disagreement like this and keep the details to themselves. Often that’s in the best interests of both parties.

There are no answers, only choices. If you’re the victim of a deadbeat, abuser, or a scammer, ethically you’re probably making the world a better place if you share that information privately, discreetly, and carefully. You could share the pertinent facts only, and only with people who have a good reason to know.

Do it for the right reasons. You’re a good citizen of a healthy planet where people are looking out for each other. You’re not a vindictive score-settler. That’s going to leave you feeling ashamed.

The Clown Coven

Our next contestant, Donetta, is here to play and lose at everybody’s favorite game. It’s called “the sunk cost fallacy.”

A raft of senior executives (I call them the Clown Coven™️) signed off on a consultant’s advice to implement an expensive off-the-shelf product. The effort was moved under Donetta’s umbrella in the project’s second year. It was a six-month project.

Donetta' has assessed a terrible mismatch between the project requirements and the platform. Sadly, the executives are joyously celebrating their great decision. They just don’t understand why it’s taking so long.

The delays are being laid at Donetta’s feet, along with a polite request for an explanation. The explanation couldn’t be simpler — they made the wrong choice. But are increasingly sad clowns are deeply, profoundly, and emotionally committed to that choice. Every two weeks they meet to confirm and ratify it again.

So what should Donetta do? She has Ivy League-caliber credentials for this thing, and the right decision is to throw away the garbage thing they bought and start over with an Open Source backend. It will probably end up costing less in the end.

When she gently raises that spectre with the Clown Coven, it does not go over well. The only thing they’re ready to do is throw a few million good dollars after the bad ones. She can keep her mouth shut, which is what it probably expected of her.

The only road we see out of here is a big old justification document that explains the Pros And Cons of Doing The Right Thing. She'd be gambling all of her political capital against the Clown Coven.

Oh, one more thing to keep in mind, if you think it matters. Donetta is a woman of color, and the Clown Coven is… well, not.

One more quote from Solaris:

How do you expect to communicate with the ocean, when you can’t even understand one another?

There aren’t any answers, my friends, only choices. Do you have any thoughts about Donetta’s situation? I’m sure she’s reading and eager to hear from you. Let’s hear yours.

Thank you, Dan Savage.